I write to praise the unloved tenses, the neglected voices, the loathed and long winded. In short*, this is a blog post about voices that are banned, styles that are shunned, and in general parts of the English language that no one wants to talk about any more.

Common writing advice:

- Use the simple past tense.

- Avoid passive voice

- Write short sentences.

- Limit paragraphs to five sentences.

Good enough advice to follow some of the time. Really bad advice to follow all of the time.

Consider, if you will, the following two sentences:

He was reading a book.

He read a book.

Both are grammatically correct. No, really. You’ll hear advice to the contrary because it is considered stronger to use the simple past tense, “He read a book.” The two tenses are both valid. It depends what you’re trying to say.

Similarly, you will be advised to always avoid passive voice. Rachel Neumeier wrote a good post about why it can be useful.

Sometimes, writing instructors can make it sound like passive voice is the work of the devil. It’s just another tool in your writer’s toolbox. There are times when you want to put the emphasis of the sentence on the object — what was done can be more important than who did it. The sentence, “The book was published in 1989.” does not tell the reader who published the book. That information is not relevant to the point the writer is trying to make.

But many people will tell you that writing is stronger if the author avoids passive voice at all times I am not kidding I mean it no not even if the room is on fire and your only escape is to use a magical password that is expressed in the passive voice.

But many people will tell you that writing is stronger if the author avoids passive voice at all times I am not kidding I mean it no not even if the room is on fire and your only escape is to use a magical password that is expressed in the passive voice.

This is a good idea taken to an undesirable extreme. You want your writing to be strong, the words to leap off the page and grab the reader’s eye before they wander off to update their Twitter account. But you don’t want your writing to be strong All The Time. You do not want your writing to be anything All The Time.

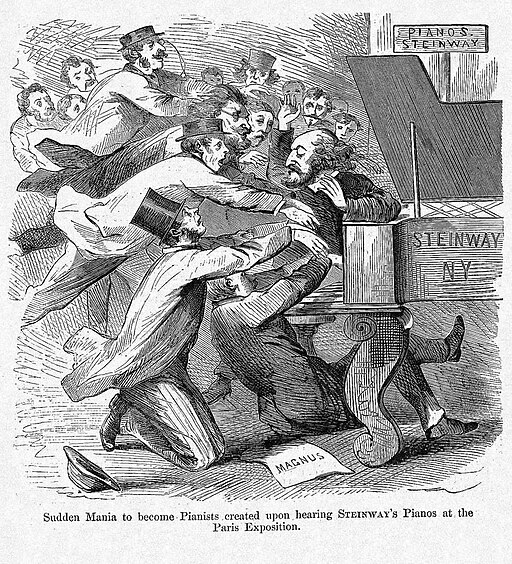

It’s like playing a piano using only chords in the major keys, avoiding any minor key that would add flavor and variety and add layers and shadows and make the experience rounded into a whole experience.

In other words, you’re limiting yourself.

Think of it like a piece of music. If you’re playing music, you do not play it all Fortissimo. Some passages are played softer, some louder. Some notes are played quickly, some slowly. The variety adds to the rhythm, carrying the reader along with it. Playing every note in the same manner is monotonous. Dull.

Think of it like a piece of music. If you’re playing music, you do not play it all Fortissimo. Some passages are played softer, some louder. Some notes are played quickly, some slowly. The variety adds to the rhythm, carrying the reader along with it. Playing every note in the same manner is monotonous. Dull.

Writing every sentence in the same way is equally dull. There are times when you want to shout and times when you want to whisper. The variety enhances the rhythm and carries the reader along.

Sometimes length can be very effective. For example, this paragraph — this is just one paragraph — from Some Buried Ceasar, by Rex Stout.

It was another fine day and the crowd was kicking up quite a dust. Banners, balloons, booby booths and bingo games were all doing a rushing business, not to mention hot dogs, orange drinks, popcorn, snake charmers, lucky wheels, shooting galleries, take a slam and win a ham, two-bit fountain pens and a Madam Shasta who reads the future and will let you in on it for one thin dime. I passed a platform whereon stood a girl wearing a grin and a pure gold brassiere and a Fuller brush skirt eleven inches long, and besides her a hoarse guy in a black derby yelling that the mystic secret Dingaroola Dance would start inside the tent in eight minutes. Fifty people stood gazing up at her and listening to him, the men looking as if they might be willing to take one more crack at the mystic, and the women looking cool and contemptuous. I moseyed along. The crowd got thicker, that being the main avenue leading to the grandstand entrance. I got tripped up by a kid diving between my legs in an effort to resume contact with mama, was glared at by a hefty milkmaid, not bad-looking, who got her toe caught under my shoe, wriggled away from the tip of a toy parasol which a sweet little girl kept digging into my ribs with, and finally left the worse of the happy throng behind and made it to the Methodist grub-tent, having passed by the Baptists with the snooty feeling of a man-about-town who is in the know.

That was one paragraph. 266 words. Stout plays with word length here, as well as paragraph length. There are three sentences averaging about 50 words per sentence, which are followed by one sentence that is 3 words long. The last sentence is 94 damn words long.

The way he structured the paragraph conveys the meaning as much as the actual words. By the time you get through it to the end, you feel exactly as if you’ve struggled through a crowd to get to your destination, which is what he was describing. Granted, if every paragraph in the story was that long, only masochists would read it. But length can be used to good effect.

Or this passage, from Patricia A. McKillip’s Fool’s Run.

He wondered at her odd silence, the sudden distance she put between them. He made a move toward her, subsided against the bar, then knew the unexpected hollow of loss at words left unspoken, action only contemplated…. The old familiar impulse to guard his actions, to hide his life, kept him a moment longer at the bar, sipping his beer, acknowledging nothing.

Then he thought, Ah, to hell with it.

In this example, McKillip employs two sentences that are 25 words long, with multiple clauses, and follows them a simple sentence 8 words long. The long sentences are contemplative, reflective; they lull you into drifting along on the sea of words. Then the terse sentence wakes you up and sends you along with the character in a new direction.

Writing. It’s not only what you say, it’s how you say it. You can alternate sentence lengths to make the writing stronger. You can use passive voice to shift the focus. You can play. You can use variety.

Really, it’s okay.

*Well, not all that short, really.